This article revises and updates Barry Buzan’s theory on the South East Asian Regional Complex or SEARC that he had framed to explain the bipolar Cold War world, by adapting it to the current behavior of states in a multipolar world amid increasing tensions with China, as well as the newly manifested construct of the ‘Indo-Pacific.’ It assesses the viability of Buzan’s theory in the context of the increasing importance of the Indo-Pacific region, and the critical role of Southeast Asian countries in regional geopolitics. It argues that the factors impacting the SEARC have evolved beyond politico-military variables, and the regional complex is designed to increase cooperation based on common agendas over outstanding political disputes. In pursuit of increasing cooperation, the complex has incorporated extra-regional powers into the region’s discourse in the context of the larger Indo-Pacific. The article identifies contemporary areas of amity and enmity in the region such as environmental degradation, economic integration in a hyper globalized environment, and the Chinese Belt and Road initiative. It argues that the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic has shown that many Southeast Asian countries have rallied to absolve China of responsibility in starting the crisis, highlighting the dependence of Southeast Asian states on the East Asian giant.

Structural realism theorizes that actors (states) exist in a natural state of anarchy, and that by means of their own capabilities, their will, and a mutually acknowledged code of conduct (by custom and/or law), they create a hierarchical structure within which they are placed. Their position is decided by their will to impact the international order, and their capabilities to actually achieve their ambitions. While Kenneth Waltz had established the theory of structural realism in the context of the politico-military and economic behavior of States during the Cold War in his book, Theory of International Politics,[1] he updated the theory in a post-Cold War scenario in his paper, “Structural Realism after the Cold War.”[2] Following this theory, and agreeing with the existence of this structure, Barry Buzan’s theory of regional security complexes around the world minimizes the global scale of analysis to specific regions of the world. It analyzes the geopolitical, economic, politico-military, and environmental factors that drive States to behave the way they do within the region they are present in. Buzan’s original definition of security complexes was “a set of states whose major security perceptions and concerns are so interlinked that their national security problems cannot reasonably be analyzed or resolved apart from one another.”[3] Furthermore, regional security theorists explain that the powers and capabilities of smaller and middle States often do not extend beyond the region they are physically present in, and more powerful States tend to exert their influence on these States and the regional complex at large by different means.[4]

Buzan updates this definition to a post-Cold War order as, “a set of units whose major processes of securitization, de-securitization, or both, are so interlinked that their security problems cannot reasonably be analyzed or resolved apart from one another.”[5] The revision in definition occurred due to the changed narrative about the role of smaller States in multipolar regions around the world, the rise of multilateralism in the east and the impact intergovernmental groups and private organizations were having on international relations, thereby diluting the state-centric assumption that had previously prevailed in academic discourse. Fundamentally, a State becomes a part of a regional security complex to ensure its own survivability, and to protect its sovereignty and economy.

Buzan in his 1988 paper on the Southeast Asian Security Complex had identified the four bases of analysis on which regional security complexes must be analyzed:[6]

This paper will amend these bases because the world order is no longer bipolar. As there exist various centers of powers, both regionally, and globally, the basis of analysis for the complex’s relationships will be combined to read as: Relationship of the complex with neighboring and extra-regional powers/players.

Although the two entities, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and SEARC, consist of the same players, conceptually they are two distinct structures. ASEAN is a formal inter-governmental organization that has its own clear set of functions and operations. And, SEARC is an academic construct that is fluid—meaning that it is not bound by a constitution or constrained by a single ideological structure—and its nature is subject to change depending on the workings of all the relevant players, including that of ASEAN as a whole. Fluidity is an outcome of State interactions without predefined boundaries. The real purpose of SEARC is to academically understand the behaviour of States in a region that is rapidly becoming the center of Asian geopolitics. SEARC offers a new and alternative method of documenting the past behavior of its constituent States and predicting the future possible paths that may be undertaken.

The theory of regional security complexes is based on the logic of States being entrenched in a web of interdependence. The interdependence may be necessary for many reasons: physical and military security, economic security, outstanding border issues, and hostile intention amongst neighboring States. Thus, States are forced to enter interdependent structures either through enmity or voluntarily through amity. For the latter, the existence of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) epitomizes the theory. The regional security organization is a manifestation of the willingness (to cooperate) of States that had mutual common agendas and concerns, in the context of the geopolitical and economic issues Europe was facing during the Cold War.

On the one hand, in the post-Cold War era, the rise of the European Union (EU) indicates the positive attitude States in the region have towards collectively tackling contemporary issues of different nature which has helped to make their union into the most developed and functional regional group in the world. While there are other groupings such as ASEAN, and the North American Free Trade Agreement, they are not as consolidated or tightly wound as their European counterpart.

On the other hand, security interdependence through enmity also tends to occur within regional sectors as well as across sectors. The uneasy tensions seen in South Asia between India and Pakistan have continued to impact the region since 1947. Since the last time these two South Asian States had gone to war in 1999, there have been spikes of tensions but never to a point as seen previously. Due to rapid globalization, the importance of Afghanistan in Indian foreign policy, and the all-weather relations between Pakistan and China, these neighboring countries seemed to be locked into a matrix of not maintaining robust bilateral relations with one another but making peace under the status-quo. Added to this mix, the nuclear deterrence exercised by India and Pakistan against one another raises an existential security dilemma when one State acts strongly against the interests of the other. Although tensions rose to astronomical heights in two instances—during the Indian Army’s surgical strikes in Pakistani territory in response to the terrorist attacks on Indian military bases by insurgent groups from Pakistan in 2016,[8] and the Indian Air Force bombardment of terrorist camps in Pakistan in 2019—the security ramifications of pursuing an all-out war was definitely a deterrent factor that underscored the security dilemma both the States faced. Thus, Pakistan pursued diplomatic action against India during those extraordinary times by approaching the United Nations with the complaint of “ecoterrorism” by India when it crossed the Line of Control and bombed terrorist outfits in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir.[9] It also unsuccessfully called upon the United Nations Security Council to censure India’s unilateral move to remove the special status accorded to the state of Jammu & Kashmir and abrogate Article 370 of the Indian Constitution.[10] Both States cannot afford to compromise the prevailing involuntary security structure they are a part of, as it poses an existential threat to their survivability.

Therefore, the three types of security interdependence can be plotted on a one-dimensional graph as shown below:[11]

This paper will analyze the dynamics of the security complex of the Southeast Asian Region and trace the evolution of the complex during the Cold War and the post-Cold War era on the lines of the above graph. The countries under study are Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, Brunei, and Myanmar. The factors and rationale that will be used for analysis are politico-military, economic, and environmental. It is important to factor in environmental concerns due to the dangerous effects of climate change on Southeast Asia’s coastal and island countries in these contemporary times, as well as how the environmental issue has become increasingly transnational in nature due to the symmetry in the impact this phenomenon has had on these States.[12] The author will further factor in the role the SEARC plays in the larger construct of the Indo-Pacific, and their part in influencing the policy initiatives of players like India, the United States, and China.

Following the model proposed by Buzan, this paper will dissect the SEARC in the following manner by examining the patterns of amity and enmity seen in military-politico relations, economic relations (bilateral and multilateral), the environment, and extra-regional partnerships or disputes:

The Southeast Asian Regional Complex during the Cold War

During the Cold War, the Southeast Asian region—like the rest of the world—was also caught in the ideological contest between the United States and the Soviet Union. While Europe moved towards multilateralism in the form of the NATO and the European Economic Community,[13] Southeast Asia was a collection of newly independent, developing countries, plagued with outstanding border issues and security concerns emanating from one another. Like Europe, modern security concerns were a mixture of rapid modernization amalgamating with ancient regional history of rivalry and contest.[14] Noting the importance of the region, the United States pursued a ‘Hub and Spokes’[15] policy in the region that placed the Western superpower at the center of international affairs in the region, and constructed strong bilateral relations with regional players, and only allowed regional interaction via itself. This inherently slowed down the inflow of multilateralism in the region and thus affected regional integration during the nascent years of the Cold War.

The rapid decolonization that followed the Second World War led to a series of disputes within and between States at a time when the Cold War was in its early phase. The long, tumultuous history of Vietnam’s struggle as a former communist state,[16] Malaysia’s internal disputes as well as that of Indonesia[17] were some of the reasons that impeded regional integration into a constructive security complex. Vietnam’s communist surge after the declaration of independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in September 1945 had become a major cause for concern for the French and later the Americans. Ho Chi Minh’s Communist Vietnam Workers Party led a revolution against French colonial rule, emancipating the northern region of the country which led to a temporary division into north and south following the Geneva Agreement in 1954.[18] The constant (indirect and direct intervention) of the United States in the domestic affairs of the Southeast Asian state, as well as establishing a narrative of creating South Vietnam as a “free and democratic state” against its northern communist counterpart led to years of strife and conflict on military-politico and ideological lines.[19] Malaysia, similarly faced ideological conflict within its borders since its inception as an independent country in 1948. Malayan emergencies were declared in rapidity, the first one lasting from 1948 to 1960,[20] and the second from 1968 to 1989.[21] The long-standing dispute between communist forces and the commonwealth forces led to years of turbulent politics and national security was often close to being compromised. Furthermore, in the interim period between the two emergencies, in 1965 Singapore separated from Malaysia to become a sovereign, city-state.[22]

The larger pattern of relations between Southeast Asian countries was shaped by internal factors of conflict along with intervention by the United States and the Soviet Union, making the region a stage for an ideological conflict between U.S. capitalism and Soviet communism by the 1960s. Support (and its lack) from the two superpowers played an integral role in the operations of the Southeast Asian countries domestically and internationally. The formation of ASEAN in 1967 indicated the ideological position of most of the countries in the region. The regional complex was divided into two parts, with the capitalist powers supporting the ASEAN members, while the Soviet Union and China backed the communist-oriented countries of Vietnam and Laos.[23] It was a series of binding agreements such as the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO) of 1954 and the Five Power Defence Arrangement of 1971 that maintained the capitalist parts of Southeast Asia as a pro-Western entity. And apart from a few instances of regional strife, such as Vietnam’s intervention in Cambodia to overthrow the genocidal Khmer Rouge in 1979,[24] Southeast Asia largely continued to remain a theatre of competition for the two superpowers through the Cold War. Such polarization devolved into different patterns of amity and enmity, most of which were moderated and contained by the United States in its ‘Hub and Spokes’ policy framework.[25] The U.S. involvement in the Second Indochina War against the northern communists was duly and unsurprisingly supported by ASEAN member countries. Singapore’s former Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew had gone on record to say that had the United States reserved its right to deploy their nuclear arsenal against North Vietnam and had there been no Watergate, the communists would not have launched an offensive in 1974.[26] Former President Richard Nixon once erroneously remarked, “Let us understand: North Vietnam cannot defeat or humiliate the United States. Only Americans can do that.”[27] Nixon found sympathetic voices of support among other ASEAN leaders as well, that also hypothesized on the alternate possible outcomes that were in favor of the capitalist agenda.[28] After the fall of Saigon, the United States and its ASEAN allies feared the next step that communist Vietnam would take, which potentially could further compromise the security of neighboring countries. They worried that the victory of the communists in Vietnam would force an upsurge in the activities of communists in Thailand and Malaysia. Furthermore, Cambodia was an emerging theatre of conflict between Vietnam and Beijing.[29] In spite of this reality, ASEAN members had already envisioned a Southeast Asia devoid of U.S. interference. ASEAN did not expect the United States to pursue a war against Hanoi indefinitely. Malaysia and Singapore, among other member states, had established a post-Nixon doctrine that looked to establish a peace-oriented structure in Southeast Asia, and also diversify its diplomatic portfolio beyond the established narratives of the bipolar world order. This led to Malaysia being the first Southeast Asian country to build diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China in 1974, followed by Thailand and the Philippines in 1975.[30]

Patterns of Southeast Asia’s relationships with external powers during the Cold War were also on the lines of the bipolarity of the world order. As earlier stated, the United States using its ‘hub and spokes’ policy had deeply integrated itself into internal workings of the regional complex as well as the bilateral interaction of these states. Furthermore, ASEAN was created on capitalist lines which in itself had polarized the region with the Vietnam-led communist bloc at the other end.

The Soviet Union’s involvement in the region developed over time. During the nascent years of the Cold War, the Soviets were focused on European issues and often relegated Southeast Asia to a secondary tier of consideration. Up until 1957, Soviet interaction with Vietnam was facilitated by China.[31] Upon Ho Chi Minh’s outreach for Soviet support, there was a certain estrangement between Hanoi and Beijing, which saw the previous status quo change, allowing an increase in the influence of Moscow in Southeast Asia.[32] Noting the extent of maritime influence the Americans could exert in the region, the Soviet Union in 1970s pursued a maritime oriented approach that emboldened its navy in the Pacific.[33] The Soviet Union further built its influence in the region by funneling more military assets to Vietnam in its campaign to invade Cambodia, which not only increased Hanoi’s dependency on Moscow but also allowed it to be in a position to rival the military power of China, the United States and ASEAN member states.[34]

During the Sino-Vietnam border conflict in 1979, a fifteen-ship Soviet fleet was dispatched to Vietnamese waters to intercept Chinese battlefield communications on behalf of the Southeast Asian state.[35] Furthermore, after the UN voted strongly in favor of an ASEAN resolution (backed by China) on Cambodia in 1980, the Soviet Union moved four warships, including their aircraft carrier Minsk into the Gulf of Thailand.[36] This was to signal a warning to Thailand and other ASEAN countries about the potential consequences of moving so close to China. Vietnam’s economic dependency on the Soviets surfaced along with its military dependence during the Cambodian invasion. The Southeast Asian state had to resist pressure from Moscow to join the Soviet-established Council for Mutual Economic Assistance or COMECON, but Hanoi joined in 1978 after it realized that it would not receive aid from the West and China. This reality compelled Vietnam to pursue stronger bilateral economic relations with the Soviet Union.[37]

The South East Asian Regional Complex in 2020

The SEARC went through drastic changes after the end of the Cold War in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union. The decade of the 1990s was a stark contrast to the political and ideological rivalries that had existed in the region. A refined attitude oriented towards the promotion of trade and economic growth engulfed the region. The complex learned to insulate itself from economic shocks from the lesson it learnt during the Asian economic crisis in 1997, and the internet bubble burst of 2002. More intra-regional and international trade, export-oriented attitude, and free market principles turned the SEARC from a politically charged complex to an economically lucrative one.[38] Furthermore, considering all states in the region are tropical and/or coastal countries, they are increasingly facing the dire effects of climate change. This existential threat is a symmetrical issue faced by all Southeast Asian countries who have initiated a conversation for a deeper and more tightly bound alliance.

On the domestic level, while there are multiple major players in the SEARC in 2020, the paper will focus on Singapore and Malaysia. The internal workings of these states largely affect the region as well as the global platform, mainly on issues of trade and commerce. Singapore’s domestic agenda ranges from a stalling technology sector, employment opportunities for native Singaporeans, housing affordability, and managing increasing social spending.[39] The Singapore Ministry of Trade and Industry is expecting growth in the technological sector after 2019’s slump but it estimates external factors to play a critical part in the stabilization of the industry. Added to this, due to rapid globalization and Singapore turning into a global employment hotspot, native Singaporeans are protesting the lack of opportunities in the skilled labor market. The government has looked to increase employment opportunities by attracting foreign direct investment and boosting trade relations within SEARC.[40] The biggest concern Singapore faces is an ageing population, and the consequent increased social spending and housing affordability. To tackle this, Singapore has ramped up housing construction and the provision of housing subsidies.

In Malaysia, the resignation of former Prime Minister Mahathir in February 2020 caused a severe change in the political landscape of the Islamic country. His resignation along with the breaking up of the coalition government forced the state into a politically chaotic position where its fragile economic position was further weakened as the ringgit continued to fall.[41] Before his resignation, Mahathir’s proposed stimulus package of US$ 4.7 billion is being honored by the new Muhyiddin administration, but uncertainty continues to loom due to the impact of the coronavirus and depleting foreign investments.[42]

Patterns of amity and enmity in the SEARC are now also defined in terms of mutual experiences of environmental degradation, and trade and commerce. ASEAN had cooperated on the environmental issue since 1977 but it had not materialized in a structured manner up until the twenty-first century. ASEAN’s current mission is to integrate sustainable development into its community. It is aiming to fulfil the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2030 by the implementing ASEAN community vision 2025 that is designed to reorient state practices towards a sustainable future.[43] Haze pollution, for example, has been a principal issue faced by SEARC countries since 1997-98, and the transnational nature of this issue has generated space for amity amongst the regional players.[44] The pollution created by the rampant slash and burn agriculture along with the environmentally detrimental practice of palm oil harvesting in Indonesia has caused the archipelagic State to adopt policy measures to protect its environmental interests as well as that of its regional neighbors.

Taking note of this issue, Singapore has even adopted legal measures to tackle this practice in the form of the ‘Transboundary Haze Pollution Act,” and while Malaysia has not looked to solidify its stance on legal or policy grounds, it has been fairly vocal and welcoming of diplomatic outreaches and engagement on this issue.[45] An ASEAN agreement backing the action against Haze Pollution is bound to consolidate the institution’s ambition of furthering patterns of amity between regional players on grounds of environmental protection.

While Buzan’s original thesis was based on the realities of a bipolar world order, this article attempts to revise the application of the theory in the context of contemporary developments in the twenty-first century and the existing multipolar world order. On the one hand, geopolitical conflict zones like the South China Sea impact the relations between the states, as seen in the case of Cambodia and Laos, due to the globalized nature of the region as well as the extra-regional hyper interest in these situations. On the other hand, the patterns of intra-regional relations are dependent on the respective country’s relations with major players like the United States and China. ASEAN has often been criticized for not taking any concrete step or action against China’s expansionist modus operandi that has compromised the physical sovereignty of various member states. ASEAN, like the United Nations, operates on the basis of the political will of its member states, and Cambodia, in particular, has barricaded substantial statements against China. For example, in 2016, ASEAN failed to find consensus on a statement against China, after Cambodia prevented the statement from mentioning the international tribunal’s ruling on the South China Sea.[46] Laos, however, has aimed to distance itself from the issue and is particularly attempting to hedge between regional players and China. On April 23, 2016, Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi confirmed that Laos had reached consensus over China’s stance on the South China Sea. Laos and China have agreed that the territorial disputes over some islands, rocks and shoals in the South China Sea are not an issue between China and ASEAN as a whole and should not affect the development of China-ASEAN relations. Laos “understands” China’s declaration that excluded compulsory arbitration in 2006 under Article 298 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.[47]

Stakeholders of the Indo-Pacific are now playing an important role in the functioning of the Southeast Asian states and the SEARC. China’s economic expansion in the form the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has taken the global economy by storm, and Southeast Asia has been a major region of focus under this initiative. Singapore, for example, has received various benefits of engaging with China, including Chinese buyers investing in Singapore’s burgeoning housing market.[48]

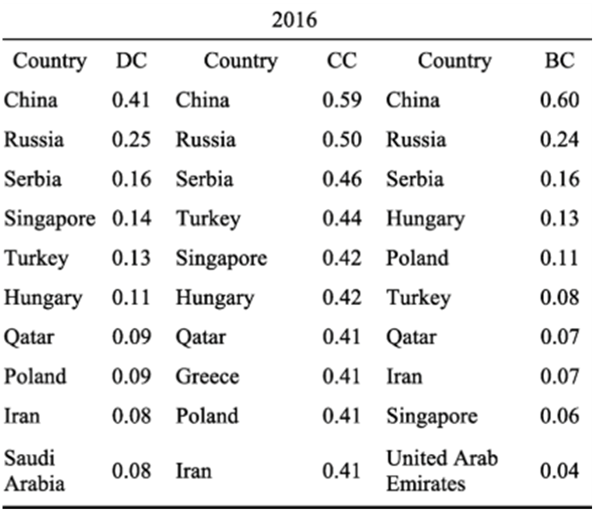

Furthermore, in a paper written by four Chinese scholars, Liu Zhigao, Wang Tao, Jung Won Sonn, and Chen Wei, designed to analyze the evolution of the BRI, a metric of centrality was established to study the role of various countries in economic trends across the world including the BRI. The centrality of major countries in the economic networks across the world influenced small states, and thus the latter gravitated towards them, becoming a part of their ‘community.’ The paper identified three kinds of centrality: degree centrality (DC) which records the number of connections one country has with others; closeness centrality (CC) which is a measure of the geodesic distance of one country to another; and betweenness centrality (BC) that measures how much a country acts as an intermediary or gatekeeper in the trade network.[49] The following table displays the top 10 countries in each kind of centrality influencing global trade in 2016:

Image 1: Degrees of Centrality in Global Trade in 2016[50]

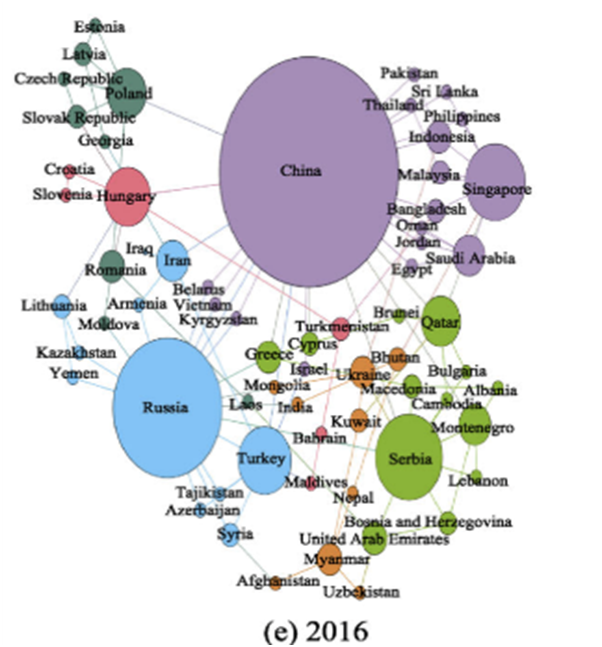

Furthermore, Image 1 shows that on a global scale Singapore’s betweenness centrality is moderate, but in Southeast Asia, it leads by a margin, and thus it is in the top ten in the world, a position which can be attributed to the trade and finance linkages occurring through the BRI. As shown in Image 2 below, Singapore strongly belongs in the Chinese trade community and has the largest bilateral linkage within that community.

Image 2: The Degree and Betweenness Centrality of Major States in the BRI Network

Economic Communities in 2016 [51]

The primary central countries are:

China-Purple

Russia-Blue

The Secondary central countries are:

Serbia: Green

Poland: Dark Green

Hungary: Pink

Singapore: Purple (in connection with China)

Turkey: Blue (in connection with Russia)

In consideration of this closeness, it is important to also note that the Ascendas group of Singapore entered into a joint venture agreement with China’s state-owned China Machinery Engineering Cooperation (CMEC) in 2015 for a strategic collaboration in investing in industrial/business parks across Asia.[52] A joint press release by the two firms noted their collaboration in countries like China, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and surprisingly India.[53] India’s image among policymakers in Singapore is benign, which is crucial for the operations India has undertaken or is going to start in the future.

The outbreak of the Corona Virus Disease of 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic continued the trend of division in the SEARC in context of the China factor as indicated by varying proactiveness displayed by all regional states. Countries that were politically allied to China, such as Cambodia and Laos, showed clear intention of maintaining positive relations with Beijing. The prime minister of Cambodia, Hun Sen, stated he would not reduce air travel to China under the six weekly flights from Wuhan. Singapore, however, right from the beginning instituted an outright ban, restricting any physical movement of potential virus carriers.[54] The disparity in reactions epitomizes the existing dichotomy in SEARC towards China, but an underlying factor that sets apart the current pandemic crisis as a case-study is the direct and immediate implications for trade relations and trade revenue for all Southeast Asian states.

The leading factors impacting SEARC states’ economies is the loss of trade/supply chains and tourism income. The pandemic broke during a financially lucrative time of year for the tourism sector and local businesses that depend on foreign visitors. Due to the lack of timely action by most states, such businesses were not sufficiently insulated from the inevitable losses that came with the virus. The SEARC, collectively, is China’s second biggest trading partner, and the latter plays a crucial role in developing modern infrastructure in various sectors in many of the region’s states. Due to the abrupt halting of Chinese projects and supply chains, the behavior of Southeast Asian states towards China has underscored the East Asian giant’s deep-sown influence in domestic politics and international relations.

It is striking that the delayed reaction of various SEARC states and ASEAN as a whole to the surging pandemic in early 2020 had contributed to the spread of the crisis in the region. Leaders in Malaysia, Indonesia, Myanmar, and the Philippines continuously downplayed or misinterpreted the gravity of the threat posed by Covid-19 during its inception. The Indonesian president, Joko Widodo, and the health minister, Terawan Agus Putranto, have been noted to have misled the public,[55] and the Indonesian authorities have previously admitted to the inadequate Covid-19 reporting by the government.[56] The Philippine president, Rodrigo Duterte used the fear of the pandemic to grant himself emergency powers, bringing him one step closer to imposing national marital law, and Myanmar officials have ambiguously stated that the indigenous diet of the state is a natural armor against the virus.[57]

The SEARC states were among the first to report cases and deaths outside of mainland China because inter-regional travel between China and SEARC contributes heavily to the economy of all countries involved—annual two-way travel flows amount to 65 million visitors.[58] The first international Covid-19 case was observed in Thailand, the first local transmission outside of China was in Vietnam, and the first international death in the Philippines.[59]

Yet, China’s extensive political influence in the region is most visible by the “expression of support” behavior exhibited by SEARC states even though there have been numerous reports and analyses demonstrating China’s callousness and negligence in handling the virus, which led to its rampant spread across the region and the globe. China rhetorically claims that it cannot be blamed for the spread of the virus or be accused of the virus originating within its borders. States like Thailand and the Philippines have backed “China’s truth,” as they seek to either absolve China’s culpability or blame other entities while not acknowledging China’s negative role in the crisis, in order to preserve close relations with the East Asian state.[60]

China’s deep-state political influence is very clearly visible in some countries. The Philippines’ health minister, Francisco Duque, refused to deny Chinese tourists entry into the country as late as January 31, 2020, as he believed “diplomatic relations with China might sour as a result and there will be serious political and diplomatic repercussions.”[61] Thailand’s health Minister, Anutin Charnvirakul, has blamed “dirty Caucasian tourists who do not shower and do not wear masks” for the rampant spread of the virus while advocating for China’s innocence.[62] Beijing’s delayed response, inaccessible data, and the political blame game has raised concerns worldwide, and in Southeast Asia. The Singapore prime minister, Lee Hsein Loong, has called for the cessation of the China-US blame game, but he also believes it is unfair to attribute all the blame for the virus’ spread to China.[63]

As China is directly impacted by Covid-19, analysts have revised downward Chinese economic growth. Its inevitable spillover into Southeast Asian economies—in the form of reduced tourist arrivals and disrupted supply chains—is bound to increase the region’s worries collectively and as singular actors. But the larger underlying issue is the soft approach of SEARC of holding China liable for its negligence in reporting the virus. This behavior is symptomatic of the economic and political dependence of the SEARC states on China at a time when their foundations, built on globalization and interconnectedness, are facing an existential threat.

ASEAN as an institution had a very slow and arguably lethargic reaction to the crisis. In February 2020, the intergovernmental organization and China issued a joint statement, agreeing on solidarity to fight the crisis, supporting micro, small and medium enterprises, and promoting e-commerce and fintech to sustain economic activities.[64]

A factor to be considered here is the impact of the crisis on the digital economy of the region. The lessons learnt from the SARS outbreak in 2003 highlight the benefits gained by digital commerce outfits, and theoretically the same would be applicable to Southeast Asian e-commerce businesses. Yet, there is a prominent difference. In 2003, e-commerce was in its nascent stages and the outbreak in China served as a coincidental boost for newly established institutions. But in 2020, in the age of digital economies and China’s hybrid Digital Silk Road,[65] the e-commerce space is not only wide open for innovation for local and regional firms, but also ripe for e-commerce giants from China such as Alibaba and JD.com, Inc.

ASEAN countries have a prescient fear of foreign powers intervening in its littorals due to either historical baggage or worries over losing control over their sovereign operations. The hesitancy by Indonesia and Malaysia to further engage with extra-regional powers has been due to these reasons and this reluctance was also displayed regarding India as well at the inception of the post-Cold War era. It was India’s interaction with Singapore and the subsequent representation by the latter in the SEARC which was the essential trigger for these countries to see India in a different light. Singapore is vital to India’s strategic ambitions in the region. The Malacca Strait is the center of the Asian maritime trade, and the Malacca dilemma is a prominent security dilemma all countries face.

Under the concept of the ‘Crescent of Cooperation,’[66]Singapore is one of the three integral countries, along with Indonesia, and Vietnam, that India must engage with to establish a quasi-deterrence-by-denial atmosphere vis-à-vis China. India’s reaction, however, to a call for action by Vietnam against China in the SEARC has been lukewarm. Despite repeated invitations in various forms from the SEARC, including from its closest allies, Singapore and Vietnam, India has been increasingly hesitant in posturing in a manner that may seem adversarial to the Chinese. Even though India has repeatedly called for freedom of navigation in the Indo-Pacific, and has found support from Singapore,[67] there still remains a great amount of ambiguity around India’s and SEARC perspective on what the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ actually constitutes and its role in regional geopolitics. Vietnam, for example, has called upon India’s Indo-Pacific architecture to rival the BRI, and the Quadrilateral formation of the U.S., Japan, Australia, and India was widely being touted as the West’s answer to China’s twenty-first century expansionism. An official from former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s administration has stated that the Quadrilateral architecture should not be viewed as a linear answer to the BRI, but rather as an alternative to the initiative that reduces the dependency of the countries receiving Chinese investments.[68]

India has remained unequivocal about the Indo-Pacific region at large and freedom of navigation within it but has remained very equivocal about structured initiatives in the Indo-Pacific, such as the Quad, a quadrilateral group consisting of India, the United States, Japan, and Australia. In August 2018, India chose to stay away from the Quad in the spirit of maintaining multipolarity in the region and establishing non-bloc security architecture.[69] This stance is considerably influenced by China’s consistent opposition to the Quad. Yet, the reality of Chinese hegemony does not cease to exist with India’s posture; China’s increasing incursions into the Indian Ocean Region is against Indian interests. Seemingly benign economic initiatives should not be viewed as hostile operations through a paranoid lens, as seen in the String of Pearls theory.[70] But it is in Indian interest to expand the reach of its capabilities with bilateral collaborations in the SEARC to not only benefit itself and the partnering country, but also increase its presence in the region and, in the long term, establish a deterrence by denial environment in the region. Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia are three principal countries that fall within this ‘crescent.’

The ‘Crescent of Cooperation’situates India’s external ambitions vis-à-vis containing China at the core of its interests and places on India the onus of constructing an economic-strategic network on a bilateral basis with Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia. [71] Such a formation would allow further economic stability in relations between the countries, and create room for changes in long-standing trends surrounding alien presence in Southeast Asia.

There is significant historical precedent about how the perception of India has changed over time, not only due to its benign regional stature and policies, but also because India’s regional outlook synchronizes well with the interests of SEARC countries. A structured policy track would pave the path for further changes in the policies of the latter in favor of India.

To initiate this long-term process, India must define with clarity what it sees as the Indo-Pacific in a constituted manner on the international stage and spell out its goals within the construct. Considering India has a growing bonhomie with SEARC countries, as in the case of Singapore and Indonesia, it should utilize its bilateral relations with the Lion City and Jakarta, in the context of the above stated policy track, to push its agenda amongst ASEAN countries. India should take these stepsin order to allow its contemporary ambitions breathing space in a new, developing and changing environment.

Ryan Mitra is a former Intern at the Southern Division of the Indian Ministry of External Affairs. He is a Bachelors’ student at Pandit Deendayal Petroleum University, School of Liberal Studies, majoring in International Relations. He has interned with the Research Centre for Eastern and North Eastern Regional Studies, Kolkata. His areas of interest are Indian foreign policy, maritime affairs, nuclear policy, and international law. His recent publications are: “India’s Persian Desire: Analysing India’s maritime trade strategy vis-aÌ€-vis the Port of Chabahar,” and “India’s Growing Maritime Opportunities with Indonesia: Room for Development in Diplomacy and Capability Building,” both published in the Maritime Affairs Journal (National Maritime Foundation); “India’s Indo-Pacific Strategy: Understanding India’s Spheres of Influence,” in The Sigma Iota Rho (SIR) Journal of International Relations (University of Pennsylvania); “The Marriage of India’s Act East and Indo-Pacific Policy,” and “China in the Maldives: Understanding India’s Security Concerns” which appeared in In the Long Run (blog of the Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Cambridge).

[1] Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (California: Addison-Wesley, 1979).

[2] Kenneth N. Waltz, “Structural Realism after the Cold War,” International Security 25, No. 1 (2000): 5-41.

[3] Barry Buzan, “Regional Security Complex Theory in the Post-Cold War Order,” in Theories of New Regionalism, ed. Fredrik Soerbaum, et al. (New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2003), 141.

[4] Safal Ghirme, “Rising Powers and Security: A False Dawn of the Pro-South World Order?” Global Change, Peace, and Security 30, No. 1 (2018), 37-55.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Barry Buzan, “The Southeast Asian Security Complex,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 10, No. 1 (1988): 4.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Nitin A. Gokhale, “The Inside Story of India’s 2016 ‘Surgical Strikes’,” The Diplomat, September 23, 2017. Also see, Press Trust of India, “Defence in 2019: Balakot air strikes, CDS and military modernization,” The Economic Times, December 31, 2019.

[9] Drazen Jorgic, “Pakistan to lodge UN complaint against India for ‘eco-terrorism’ forest bombing,” Reuters, March 1, 2019.

[10] Elizabeth Roche, “At UNSC, China and Pakistan failed to censure India over Article 370,” Livemint, August 17, 2019.

[11] D. Frazier and R. Stewart-Ingersoll, “Regional Powers and Security: A Framework for Understanding Order Within Regional Security Complexes,” European Journal of International Relations 16, No. 4 (2010): 731-753.

[12] Amit Prakash, “Boiling Point,” Finance and Development 55, No. 3 (2018): 22-26. Accessed February 10, 2020, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2018/09/southeast-asia-climate-change-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions-prakash.htm.

[13] Gordon L Weil, A Handbook on the European Economic Community (Washington DC: Fredrick A. Praeger, 1965). Also see, Douglas Lute and Nicholas Burns, “NATO at Seventy: An Alliance in Crisis,” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, February 2019, https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/NATOatSeventy.pdf.

[14] Buzan, “The Southeast Asian Security Complex,” 4.

[15] Victor Cha, Powerplay: The Origins of the American Alliance System in Asia, (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2016), 3.

[16] Nick Davies, “Vietnam 40 Years On: How a Communist Victory gave way to Capitalist Corruption,” The Guardian, April 22, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2015/apr/22/vietnam-40-years-on-how-communist-victory-gave-way-to-capitalist-corruption.

[17] Buzan, “The Southeast Asian Security Complex,” 5.

[18] Alan Watt, “The Geneva Agreement 1954 in Relation to Vietnam,” The Australian Quarterly 39, No. 2 (1967), 12.

[19] Davies, “Vietnam 40 Years On: How a Communist Victory gave way to Capitalist Corruption.”

[20] R.W. Komer, “The Malayan Emergency in Retrospect: Organization of a Successful Counterinsurgency Effort,” Rand, February 1972, 9. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reports/2005/R957.pdf.

[21] Ong Weichong and Kumar Ramakrishna, “The Second Emergency (1968-1989): A Reassessment of CPM’s Armed Revolution,” RSIS Commentaries 191 (2013).

[22] “Singapore Separates from Malaysia and Becomes Independent,” History SG, accessed February 16, 2020, http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/dc1efe7a-8159-40b2-9244-cdb078755013.

[23] Buzan, “The Southeast Asian Security Complex,” 5.

[24] Nayan Chanda, “Vietnam’s Invasion of Cambodia, Revisited,” The Diplomat, December 1, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/12/vietnams-invasion-of-cambodia-revisited/.

[25] Cha, Powerplay: The Origins of the American Alliance System in Asia, 19.

[26] Ang Cheng Guan and Joseph Chinyong Liow, “The Fall of Saigon: Southeast Asian Perspectives,” Brookings, April 21, 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/the-fall-of-saigon-southeast-asian-perspectives/.

[27] James Lindsay, “The Vietnam War in 40 Quotes,” Council of Foreign Relations, April 30, 2015, https://www.cfr.org/blog/vietnam-war-forty-quotes.

[28] Ang, “The Fall of Saigon.”

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Paul Keleman, “Soviet Strategy in Southeast Asia: The Vietnam Factor,” Asian Survey 24, No. 3 (1984), 335.

[32] Ibid.

[33] S. G. Gorshkov, “The Sea Power of the Soviet State,” Survival 19 (1977).

[34] Keleman, “Soviet Strategy in Southeast Asia,” 342.

[35] S. W. Simon, “Southeast Asia in Soviet Perspective,” in Soviet Policy in the Third World, ed. W. R. Duncan (New York: Pergamon, 1980), 241.

[36] Lau Teik Soon, “ASEAN and the Cambodian Problem,” Asian Survey 22, No. 6 (1982), 559.

[37] Keleman, “Soviet Strategy in Southeast Asia,” 342.

[38] Sandra Seno-Alday, “What ASEAN Can Teach the World About Surviving a Financial Crisis,” The Diplomat, September 28, 2015.

[39] Siow Yue Chia, “What Are Singapore’s Domestic Priorities for 2020,” The Diplomat, January 10, 2020.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Eustance Huang, “Malaysian Ringgit Set to Weaken further as Political Chaos, and Coronavirus take hold, says Aberdeen,” CNBC, February 26, 2020.

[42] Market Movers, “Malaysia’s new PM takes office amid economic challenges,” Reuters, March 2, 2020.

[43] Simon S.C. Tay, et al., “ASEAN Approaches to Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development: Cooperating across Borders, Sectors, and Pillars of Regional Community,” in Global Megatrend: Implications for the ASEAN Economic Community, 100.https://asean.org/storage/2017/09/Ch.4_ASEAN-Approaches-to-Environmental-Protection-and-Sustainable-Dev.pdf.

[44] Ibid,106.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Manuel Mogato, et al., “ASEAN Deadlock on South China Sea, Cambodia Blocks Statement,” Reuters, July 25, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southchinasea-ruling-asean/asean-deadlocked-on-south-china-sea-cambodia-blocks-statement-idUSKCN1050F6.

[47] Ge Hogilang, “Laos Strikes Careful Balance on South China Sea Disputes as ASEAN Chair,” Global Times, May 4, 2016, http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/981392.shtml.

[48] Grace Shao, “Chinese Investors choose Singapore over Hong Kong for ‘diversification’- but things could change,” CNBC, November 24, 2019, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/25/chinese-investors-picking-singapore-property-over-hong-kong-for-now.html.

[49] Zhigao Liu, et al., “The Structure and Evolution of Trade Relations between Countries along the Belt and Road,” Journal of Geographical Sciences 28, No. 9 (September 2018): 1240, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-018-1522-9.

[50] Ibid, 1242.

[51] Ibid, 1242.

[52] Angela Tan, "Ascendas in JV with China Machinery to Invest in Asian Industrial/Business Parks," Business Times, November 9, 2015, <https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/government-economy/ascendas-in-jv-with-china-machinery-to-invest-in-asian-industrialbusiness-parks> accessed 11 April 2019.

[53] China Machinery Engineering Corporation, "Ascendas and China Machinery Engineering Corporation Inked Strategic Industrial/Business Park Collaborative Agreement for Asia," (2015), <https://www.ascendas-singbridge.com/-/media/ascendas/files/press-release/press-release-2015/press-release---ascendas-cmec-jv-press-release.ashx>.

[54] Parmesha Saha, “COVID 19: Impact and responses in Southeast Asia amidst China’s ‘soft power’ diplomacy,” Observer Research Foundation, March 21, 2020, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/covid19-impact-response-southeast-asia-amidst-china-soft-power-diplomacy-63570/.

[55] Joshua Nevett, “Coronavirus: I watched the president reveal I had COVID-19 on TV,” BBC, May 6, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-52501443.

[56] “Indonesia: Little Transparency in COVID-19 Outbreak,” Human Rights Watch, April 9, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/09/indonesia-little-transparency-covid-19-outbreak.

[57] Saha, “COVID 19: Impact and responses in Southeast Asia amidst China’s ‘soft power’ diplomacy.”

[58] Lucio Blanco Pitlo, “China, ASEAN Band Together in the Fight Against Coronavirus,” The Diplomat, March 4, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/03/china-asean-band-together-in-the-fight-against-coronavirus/.

[59] Pitlo, “China, ASEAN Band Together in the Fight Against Coronavirus.”

[60] Sophie Boisseau du Rocher, “What COVID-19 Reveals About China-South East Asia Relatons, ” The Diplomat, 8 April 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/what-covid-19-reveals-about-china-southeast-asia-relations/.

[61] Ben Rosario, “Duque rejects ban on Chinese tourists, cites diplomatic, political repercussions,” Manila Bulletin, January 31, 2020, https://news.mb.com.ph/2020/01/29/duque-rejects-ban-on-chinese-tourists-cites-diplomatic-political-repercussions/.

[62] Richard S. Ehrlich, “Thailand blames its COVID-19 crisis on Caucasians,” Asia Times, March 20, 2020, https://asiatimes.com/2020/03/thailand-blames-its-covid-19-crisis-on-caucasians/

[63] Bhavan Jaipragas, “Coronavirus: Singapore PM calls for end to US-China blame game, wants to see leadership from Trump administration,” South China Morning Post, March 30, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/3077479/coronavirus-singapore-pm-calls-end-us-china-blame-game.

[64] Pitlo, “China, ASEAN Band Together in the Fight Against Coronavirus.”

[65] Xianbai Ji, “Will COVID-19 be a Blessing in Disguise for the Belt and Road?” The Diplomat, May 2, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/05/will-covid-19-be-a-blessing-in-disguise-for-the-belt-and-road/.

[66] Japish S. Gill and Ryan Mitra, "India's Indo-Pacific Strategy: Understanding India's Spheres of Influence," Sigma Iota Rho Journal of International Relations, 2018, <http://www.sirjournal.org/research/2018/7/5/indias-indo-pacific-strategy-understanding-indias-spheres-of-influence>.

[67] Prashanth Parameswaran, "India-Singapore Relations and the Indo-Pacific: The Security Dimension," The Diplomat, November 27, 2018, <https://thediplomat.com/2018/11/india-singapore-relations-and-the-indo-pacific-the-security-dimension/>.

[68] Jane Wardell and Colin Packham, "Australia, US, India and Japan in Talks to Establish Belt and Road Alternative: Report" Reuters February 19, 2018, <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-beltandroad-quad/australia-u-s-india-and-japan-in-talks-to-establish-belt-and-road-alternative-report-idUSKCN1G20WG>.

[69] Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, "India Not to Join US-Led Counter to China’s BRI," The Economic Times, April 7, 2018).

[70] Ryan Mitra and Japish S Gill, "The Strength Of The String: The Realities Of The String of Pearls Theory," The Calcutta Journal of Global Affairs 3. No. 1 (January 2019):51-68.

[71] Ibid.